HISTOIRE - Michel GAUTIER

Inauguration du Mémorial du Lancastria

16 juin 2016

Clic sur les fichiers ci-dessous

![]() Dossier de presse du Lancastria

Dossier de presse du Lancastria

*******************************************

Récit historique Lancastria

Le naufrage du Lancastria (English version at the end)

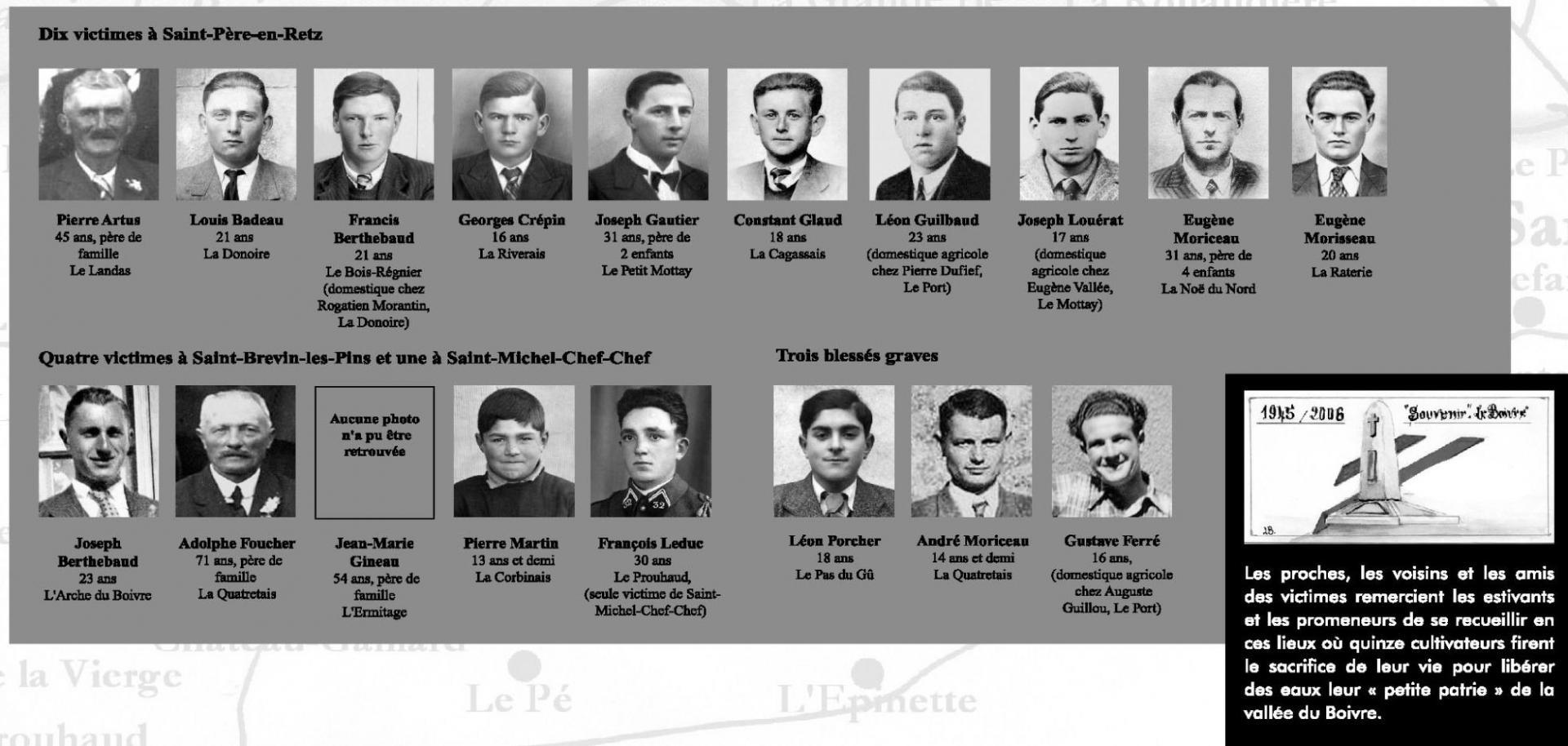

Depuis le 10 mai 1940, l’armée allemande déferle sur la France. Le réembarquement d’une partie du corps expéditionnaire britannique s’est achevé le 4 juin 1940 à Dunkerque (opération Dynamo) et le 13 juin au Havre (opération Cycle). Cette évacuation va se poursuivre entre le 16 et le 25 juin, lors de l’opération Aerial à partir des ports de Cherbourg, Saint-Malo, Brest, Saint-Nazaire, La Pallice, Bordeaux, Bayonne et Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

Paris vient de tomber. Constatant l’inanité d’un « réduit breton » indéfendable, Churchill a en effet ordonné au général Brooke de rapatrier au plus vite les restes du corps expéditionnaire. Cette opération Aerial va permettre à près de 200 000 soldats alliés de rejoindre l’Angleterre (britanniques mais aussi polonais, français, tchèques, belges…)

Le 17 juin 1940, alors que la Wehrmacht vient de pénétrer en Bretagne, le maréchal Pétain appelle à cesser le combat et demande l’armistice. Il est 12 h 30. Le lendemain 18 juin à 18 h, le général de Gaulle lancera son appel sur les ondes de la BBC : « Cette guerre est une guerre mondiale… Quoi qu'il arrive, la flamme de la résistance française ne doit pas s'éteindre et ne s'éteindra pas ». Entre ces deux appels se seront écoulées trente heures où aura basculé le sort du pays… Et la flotte britannique aura connu le naufrage le plus coûteux en vies humaines de son histoire.

Le 16 juin, on attend à Saint-Nazaire environ 15 000 soldats britanniques. À la fin de l’opération on aura évacué plus de 40 000 hommes : une majorité d’Anglais, mais aussi des Polonais et des Tchèques, ainsi que quelques civils. Ils battent en retraite en camion, en voiture, en moto mais le plus souvent à pied. Ils sont rejoints par les personnels des hôpitaux militaires et des dépôts de la région. Les soldats détruisent ou abandonnent sur place armes et munitions, véhicules, carburant….

Parmi une flotte de navires de toutes tailles, quatre paquebots mouillent l’ancre en rade de Saint-Nazaire : le Botary, le Georgic, le Duchesse d’York et le paquebot polonais Sobieski. Malgré le risque des mines, le transbordement commence le 16 juin à 11 h, assuré par trois torpilleurs de la Royal Navy et trois remorqueurs français. Le lendemain 17 juin, la flotte a encore grossi et certains bateaux accostent à même la forme entrée du port. Parmi une vingtaine de navires mouillant dans la rade, on reconnaît l’Oronsay et le Lancastria, un ancien « liner » de 16 000 tonnes transformé en 1932 en paquebot de croisière de la Cunard. Les transbordements achevés, les deux navires feront route en convoi pour réduire le risque de torpillage par des sous-marins ennemis…

À 13 h 48, première alerte ! Un bombardier allemand largue 4 bombes sur l’Oronsay dont une explose sur le pont et une autre sur la timonerie, entièrement détruite. Sur le pont du Lancastria, le capitaine Rudolph Sharp est prêt à faire appareiller son bateau plein à ras bord. Le matin même, deux officiers seraient montés à bord de l’ancien paquebot de luxe prévu pour 2500 personnes pour demander au capitaine d’embarquer autant de soldats que possible… Soudain, à 15 h 48, trois Junkers 88A de l’escadrille II./KG30 du 4. Fliegerkorps en provenance de la base de Chièvres en Belgique, fondent à nouveau sur la flotte ; leurs pilotes sont spécialement entraînés à l’attaque des bateaux d’évacuation du corps expéditionnaire britannique.

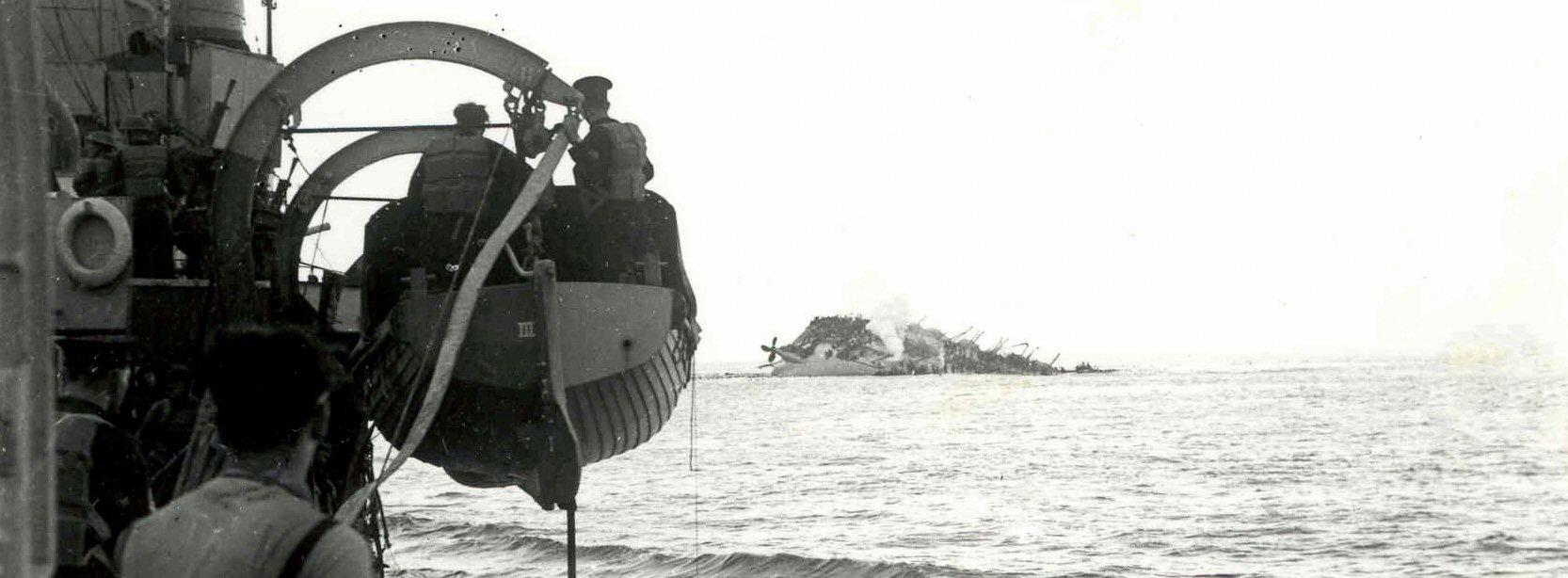

Les mitrailleurs de pont du Lancastria ouvrent le feu mais ne peuvent empêcher le deuxième bombardier de lâcher 4 bombes. La première éclate dans la cale N° 2 au milieu de 800 hommes de la RAF. La deuxième transperce la cale n° 3, libérant 500 tonnes de mazout qui envahissent le navire. La troisième tombe tout près de l’unique cheminée pour exploser dans la salle des machines. La quatrième éventre la cale N° 4 où la mer s’engouffre. Au moins un millier d’hommes sont déjà morts ou blessés. Tandis que se répand un mazout gluant et épais, le Lancastria s’incline à bâbord. En 24 minutes, il aura disparu de la surface des flots.

Après avoir chanté des chants populaires ou patriotiques (Roll out the barrel, There will always be an England) et des hymnes religieux pour se donner du courage, tous ceux qui le peuvent se jettent à l’eau avant que le navire ne sombre dans la baie des Charpentiers. Une nouvelle vague de bombardiers Heinkel III largue alors des bombes incendiaires, heureusement sans effet sur une couche de 20 cm de mazout où se débattent les rescapés s’accrochant à tout ce qui flotte. À la suite du bateau pilote La Lambarde et du destroyer Highlander, tous les navires se portent au secours des naufragés, tandis que les avions mitraillent les survivants.

On va repêcher 2477 rescapés. Mais combien d’hommes à bord ? On avait arrêté les enregistrements vers 6000, mais on avait continué pourtant d’embarquer… Sept mille ? Huit mille ? Neuf mille hommes ? Les documents de bord sous secret militaire ne s’ouvriront qu’en 2040. Pendant des mois, on va retrouver des centaines de cadavres sur les plages et dans les filets des pêcheurs. Ils sont enterrés dans 53 cimetières entre Brest et Soulac, dont 16 de part et d’autre de l’estuaire de la Loire. Mais au large de la pointe Saint-Gildas, à 9,5 miles au SW de Saint-Nazaire, par 24 m de fond, le long du chenal des Grands Charpentiers, gît encore l’épave éventrée déclarée « tombe de guerre ». (47°08 N, 2°20 W, au large des Evens).

Le naufrage du Lancastria a fait probablement plus de 4 000 victimes (trois fois plus que celui du Titanic et plus du tiers des pertes du Corps expéditionnaire britannique en France en 1940) et c’est l'un des naufrages les plus meurtriers de l'histoire. Churchill ne voulant pas saper le moral de son peuple garda ce lourd secret jusqu’à la fin de la guerre. Pour notre région, c’était le coup de gong de la guerre et le début d’un récit mémoriel inscrit désormais dans ce panneau historique.

The sinking of the Lancastria

The German army had been sweeping through France since the 10th of May 1940. The re-embarkation of part of the British Expeditionary Force ended on the 4th of June 1940 in Dunkirk (Operation Dynamo) and on the 13th of June in Le Havre (Operation Cycle). This evacuation was to continue between the 16th and 25th of June during Operation Aerial from the ports of Cherbourg, Saint-Malo, Brest, Saint-Nazaire, La Pallice, Bordeaux, Bayonne and Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

Paris had just fallen. Realizing the futility of an indefensible “Breton position”, Churchill ordered General Brooke to repatriate as quickly as possible the remainder of the Expeditionary Force. Operation Aerial enabled around 200 000 allied soldiers to rejoin Britain (British soldiers but also Polish, French, Czech, Belgians...).

On the 17th of June 1940, while the Wehrmacht had just gone into Brittany, Marshal Petain was calling for a cease fire and asking for armistice. It was 12:30. The next day on the 18th of June at 18:00 hours, General de Gaulle sent his appeal on the BBC airwaves : “This war is a world war... Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished and will not be extinguished”. Between these two appeals 30 hours apart, the fate of France had changed radically... And the British fleet will have experienced the most costly sinking in terms of human lives in its history.

On the 16th of June, about 15 000 British soldiers are expected in Saint-Nazaire. At the end of the operation more than 40 000 men will have been evacuated : mostly British but also Polish and Czech, as well as a few civilians. They retreat by trucks, cars, motorbike but more often on foot. They are joined by the staff from military hospital and regional bases. The soldiers destroy or abandon on the spot arms and ammunitions, vehicles, fuel...

Among a fleet of various sizes, four liners lie at anchor in the port of Saint-Nazaire : Botary, Georgic, Duchess of York and the Polish liner Sobieski. Despite the threat of mines, the embarkation starts on the 16th of June at 11:00 hours, help provided by three Royal Navy torpedo boats and three French tug boats. The next day on the 17th of June, the fleet has increased and a few ships even anchor at the entry to the port. Amid twenty or so ships moored in the port, are Oronsay and Lancastria, an old liner of 16 000 tons transformed in 1932 as a cruise ship for the Cunard company. The embarkation finished, the two ships are meant to sail together to reduce the risk of being torpedoed by enemy submarines...

At 13:48, first air raid warning ! A German bomber drops 4 bombs on Oronsay, one exploding on the deck and another on the wheelhouse destroying it completely. On the deck of Lancastria, Captain Rudolph Sharp is ready to sail, his ship full to the brim. That very morning, two officers had boarded the old luxury liner meant for 2500 passengers to ask the captain to embark as many soldiers as possible... Suddenly, at 15:48, three Junkers 88A from the squadron 11./KG30 of the 4. Fiegerkorps from Chievres base in Belgium, swoop down on the fleet ; their pilots specially trained to attack evacuation ships of the Expeditionary Force.

The Lancastria gunners open fire but cannot stop the second bomber from dropping 4 bombs. The first one explodes in hold n° 2 in the middle of 800 RAF men. The second pierces hold n° 3, releasing 500 tons of heavy oil that spread out in the ship. The third bomb falls very near the only funnel to explode in the machine room. The fourth rips out hold n° 4 where the sea rushes into the ship. At least a thousand men are already dead or injured. Whilst the thick and sticky heavy oil spreads out, Lancastria lists port side. In 24 minutes it will have been submerged by the sea.

After singing popular or patriotic songs (Roll out the barrel ; There will always be an England) and religious hymns to give themselves strength and courage, all those who can, throw themselves in the sea before the ship sinks in the Bay des Charpentiers. Then a new wave of bombers Heinkel 111 drop incendiary bombs, fortunately without effect on a 20 centimetres layer of heavy oil, where survivors are struggling, clinging to everything floating. Following the example of the tug boat La Lambarde and the destroyer Highlander, all ships go to the rescue of the survivors whilst the planes bombard them.

2477 survivors will be rescued. But how many men were on board ? The recording of the names stopped at around 6000, but the embarkation of men continued... 7 000, 8000, 9000 men ? The ship papers are under military secret and will not be opened before 2040. For months and months hundreds of bodies will be found on beaches and in the fishermen’s nets. They are buried in 53 cemeteries between Brest and Soulac, the greatest number lie in 16 cemeteries on either side of Saint-Nazaire estuary. However off the coast of La Pointe Saint-Gildas, 9.5 miles SW of Saint-Nazaire, 24 m deep, along the Grands Charpentiers channel, lies the smashed up wreck of the Lancastria, listed “war grave” (47°08N, 2°20W, off the Evens).

With the sinking of the Lancastria, probably more than 4000 men perished (3 times more than the sinking of the Titanic had and more than a third of the British Expeditionary Force perished in France in 1940). It is one of the most murderous sinking in history. Churchill, not wanting to undermine the morale of his nation, kept that heavy secret until the end of the war. For our region, it was the stroke which made people aware that the war was really on and henceforth the start of a memorial narrative written in this historical plaque.

A red buoy indicates the site of the shipwreck. The Lancastria lies 24 m deep, 17 km south of Saint-Nazaire and 7 km west of La Pointe Saint-Gildas.

*******************************************